- Home

- Peter Burns

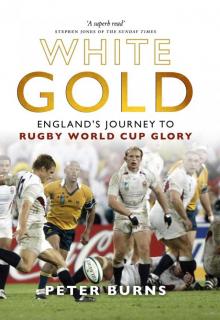

White Gold

White Gold Read online

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Peter Burns, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-909715-08-0

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-694-6

The right of Peter Burns to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Grateful acknowledgements are made to HarperCollins for extracts from Full Time: The Autobiography by Jason Leonard and Nine Lives: The Autobiography by Matt Dawson; Orion for Richard Hill: The Autobiography and Clive Woodward: The Biography by Alison Kervin; Hodder Headline for It’s in the Blood: The Autobiography by Lawrence Dallaglio, Winning! The Autobiography by Clive Woodward, Martin Johnson: The Autobiography and Jonny: My Autobiography by Jonny Wilkinson.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburgh

01010100 01101000 01100001 01101110 01101011 00100000 01111001 01101111 01110101

00100000 01100110 01101111 01110010 00100000 01100001 00100000 01110111 01101111

01101110 01100100 01100101 01110010 01100110 01110101 01101100 00100000 01100101

01100100 01101001 01110100 00101100 00100000 01001010 01110101 01101100 01101001 01100101

Printed in Sweden by Scandbook

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks, first of all, must go to my grandmother, Pamela Walker – for although she has lived in Scotland for over 60 years, she has always remained a true English rose; and as her heritage qualifies me under IRB rules to play for England, I therefore feel, by extension, qualified to write about England rugby’s most glorious years.

Thank you to Tom English and Stephen Jones for supporting the idea of this book from the outset and for their kind endorsements of the finished product. Tom’s marvelous account of the 1990 Grand Slam show-down between Scotland and England, The Grudge, had a significant influence on the style of this book, as did Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, Alan English’s Stand Up and Fight and John Carlin’s Playing the Enemy (which became the film, Invictus). Matthew Syed’s Bounce, Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and Daniel Coyle’s The Talent Code also inspired my approach – an eclectic mix, there’s no doubt, but all had a part in the formation of ideas that went into creating White Gold. Moneyball was the first flash of inspiration – Clive Woodward is my rugby equivalent of Billy Beane – but these books all helped to fuel the fire.

A special thank you must go to Sir Clive Woodward for setting aside time to meet with me and for speaking so openly.

I am indebted to a long list of biographies, autobiographies, scientific studies, documentaries and dozens and dozens of newspaper and magazine columns which formed the basis for much of my research. A list of these sources can be found in the end-matter of this book – it is a long list and while I would recommend just about every one of the autobiographies and histories, for those who would like to learn more about the broader issues discussed herein – particularly those that draw on accounts and studies that go beyond the rugby matches themselves – I would nudge you towards Bounce, Outliers, Winning! and The Talent Code.

Thanks to all at Arena Sport and Birlinn Ltd who backed me on this project and have bought their renowned enthusiasm and high standards to bear on the end product. I hope that I have repaid their faith.

Finally, thank you to Annabelle, Isla and Hector who put up with me while I wrote this book. I’m sure that, by comparison, they think that England’s journey was a walk in the park...

‘Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs even though chequered by failure, than to rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy nor suffer much because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.’

Theodore Roosevelt

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

PART ONE: GENESIS

ONE: THE ANATOMY OF A PHILOSOPHY

TWO: THE ANATOMY OF A BUSINESSMAN

THREE: THE ANATOMY OF A COACH

PART TWO: REVOLUTION

FOUR: THE ANATOMY OF AN UPHEAVAL

FIVE: THE ANATOMY OF A WINNING CULTURE

SIX: THE ANATOMY OF BUILDING A WORLD-CLASS TEAM

SEVEN: THE ANATOMY OF EXCELLENCE

EIGHT: THE ANATOMY OF PREPARATION

PART THREE: ASCENSION

NINE: THE ANATOMY OF THE CLIMB

TEN: THE ANATOMY OF THE SUMMIT

PART FOUR: HUBRIS

ELEVEN: THE ANATOMY OF THE THEREAFTER

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PROLOGUE

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He who can call today his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

Tomorrow do thy worst, for I have lived today.

Be fair or foul or rain or shine

The joys I have possessed in spite of fate, are mine.

Not Heaven itself upon the past has power,

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

Horace, Odes, Book III, xxix

Manly. Friday, 21 November 2003.

Within throwing distance of the golden sands that hem the eastern side of the Manly peninsula – a ribbon of land that juts out into the Tasman Sea on the north-east edge of Sydney Harbour – sits Manly Rugby Football Club.

A blustery wind was blowing in from the ocean on this late spring afternoon, rolling great white-crested waves on to Manly Beach and swelling the waters around a ferry that was carrying commuters from Manly Wharf to Circular Quay in downtown Sydney some seven miles away. The wind whipped up the sand on the beach and then swept inland, swirling across the pitch at the Manly Oval and then onwards towards the inland suburbs.

The view from club’s stand, which faced east towards the Tasman, was one of the finest to be found in any sporting venue in the world – even on an unseasonably cold day like this when heavy slate-grey clouds cast a gloomy pall over the land below. The Oval had an unusual appearance, with temporary barriers erected all around its outer perimeter and patrolling security guards keeping a close eye as flocks of white-shirted fans gathered along the pavement, trying to get close enough to the barriers to peer through to the pitch at the centre of the Oval.

Huddled together in the stand, arms crossed against the wind, sat half a dozen figures. Frowns of concentration were etched across their faces as they peered down at the group of thirty men jogging around the field. There were two distinct teams of fifteen at work, running through a series of practice attack and defence moves.

After a babble of instructions, eight forwards on one side jogged lightly to the touchline for a line-out and seven backs assembled themselves into an attacking formation outside them. In opposition stood fifteen understudies, each with a yellow bib over his training gear, and in equally swift fashion they arranged themselves into a defensive configuration.

The murmur of Manly’s traffic could be heard

undulating in the background, mixing with the sound of the wind, the ocean, the occasional blast of horns from the commuting ferries and sporadic cries from the fans on the other side of the barriers. Down on the pitch the players barked instructions to one another – the attacking line-out code was called along with a corresponding backline move; each man in the defensive side called out who they were marking, while the inside-centre, Stuart Abbott – the general of the defensive line – reiterated the need for line-speed to close down the attack, and then readied himself to lead the charge as soon as the ball was released into play.

This was the England rugby squad. They were some twenty-eight hours away from the biggest match of their lives, the 2003 World Cup final, which was to be played against Australia, the host nation of the tournament, holders of the Webb Ellis Cup and the current world champions. Of all the outcomes of tournament rugby, to face the title holders – one of the undisputed superpowers of the world game – on their home ground in front of a partisan local crowd and under a welter of global media coverage, pressure and expectation, was as big as it could get.

Louise Ramsay, the England team manager, appeared from the tunnel beneath the stand and made her way up the steps to the group of seated observers. The first to greet her was Dave Alred, the kicking guru. ‘Any news on the weather?’ he asked, his eyes rising balefully to the dark clouds above them.

‘More rain,’ said Ramsay flatly, handing him a printout of the forecast.

Next to Alred, Andy Robinson, the forwards coach, nodded in brief acknowledgement but said nothing. For a moment a thin smile had registered on his lips as he cast his mind back just two months to Pennyhill Park in Surrey, where the squad had been training throughout one of the hottest English summers on record. Although training in such conditions had been hellish for the players, the management group had been delighted that the sweltering temperatures would match the conditions expected in Australia, glad that the team would be acclimatised before boarding the plane at Heathrow. So much for that theory. Since the team had flown into Perth some six weeks earlier, they had played almost exclusively in conditions that would have had Noah making final preparations to the ark. At this stage of the tournament the prospect of more rain was no surprise. The semi-final five days earlier had been played in a torrential downpour. Indeed, it had felt just like being back at Twickenham for an early February Calcutta Cup clash. As the forwards coach of the most effective and most experienced pack at the World Cup, Robinson was not remotely concerned at having to play in the kind of conditions typical at home during the autumn internationals or the Six Nations. Every player in the squad was comfortable with the ball in hand and over the previous few seasons England had developed a style of play never before practised by their predecessors: a heady combination of speed and width, flat passing, aerial bombardments, devastating running angles and brutal defence. But they had not forgotten the traditional cornerstone of the English game: brute power up front. If the conditions dictated a forwards-orientated slugfest, Robinson knew that he had some of the planet’s finest exponents of granite-hard forward domination in his ranks.

His eyes didn’t move from the players below as Ramsay and Alred discussed the possible wind conditions at the Telstra Stadium in central Sydney the following evening. He was watching his charges as they took their places at the line-out. In the middle of the line, Phil Vickery, the tight-head prop, feinted forward for a moment and then spun on his heels and took two quick steps towards the towering figure of lock Ben Kay. Steve Thompson, the hooker, drew back his arms and fired the ball in a smooth, spiralling torpedo that sailed in a high arc between the two contesting packs in front of him. Kay leapt, his jump propelled by Vickery, who gripped his legs just below his kneecaps and thrust him as high as his arms would stretch, while blindside flanker Richard Hill offered support from behind, his hands on Kay’s hamstrings, pushing him as high as he could manage. In opposition, substitute prop Jason Leonard and flanker Lewis Moody boosted Kay’s understudy, Simon Shaw, up to contend for the ball.

At the apex of the jump, Kay stretched out a hand and plucked the ball from the air before dropping it deftly down to the waiting scrum-half Matt Dawson, who immediately whipped the ball out to his backline. The whole process had taken little more than two seconds and had been executed to absolute perfection. Like a well-oiled machine, thought Robinson. Shaw’s jump had been good, the supporting lift strong, but the slickness with which Vickery, Kay, Hill and Thompson had executed their routine had left the giant figure of Shaw grasping nothing but thin air.

‘It’s going to be pretty rough going,’ continued Ramsay over Robinson’s shoulder. ‘Similar conditions to the semi.’

‘Fine,’ said Alred, and stood up. Wind and rain. Hardly a kicker’s conditions of choice, but for the man that Alred worked with, who had first come under his guidance as a callow teenager, it would matter little. Come rain, wind or hail, England’s stand-off, Jonny Wilkinson, could – and would – strike the ball with the same deadly accuracy and efficiency as he would on a calm, bright summer’s day. No matter what.

Alred shoved a little sheaf of notes into the zip pocket of his windcheater and began to make his way down towards the pitch.

The ‘captain’s run’ was drawing to a close. The coaches had long ago ceased to intervene at this stage of the team’s pre-match preparation; it was a time for the players to run their final moves, to ensure that everything was working like clockwork. At this stage, the coaches didn’t need to tell the likes of Martin Johnson, Lawrence Dallaglio, Neil Back, Hill, Dawson or Will Greenwood what to do. Indeed, none of the players out there – including the fifteen who were running in opposition – needed any further guidance from those in the stands. Every pattern of play was second nature; every call and move and reaction a natural progression from one to the other. They were a well-oiled machine indeed.

A ruck formed on the far 22-metre line and as Dawson bent to retrieve the ball from where centre Mike Tindall had placed it he heard the trigger-call for immediate distribution from Wilkinson and the ball was spun away from the breakdown almost as soon as Dawson had touched it.

Wilkinson shifted the ball to his inside-centre, Greenwood, who straightened the line, jinked and then dropped a soft little pass to full-back Josh Lewsey, who hit the line at an angle off Greenwood’s shoulder and sliced straight through the onrushing defence. As his opposite number, Iain Balshaw – the last man in the defensive line – swept across to close down his space, Lewsey found that he had support runners on either flank – Jason Robinson on his left, Ben Cohen on his right. The two wingers were completely different in stature and brought contrasting styles of play to the strike-runner positions of left and right-wing, but both were equally lethal with ball in hand. After a small feint to Robinson, Lewsey fixed Balshaw with a half-step and then shifted the ball to Cohen and the six-foot-two, sixteen-stone speedster cruised in unopposed under the posts.

Johnson, the captain, was emerging from the ruck back on the 22. He nodded, a glint of satisfaction flickering for a moment in his dark eyes before his brow contracted into its habitual furrows, and with a wave of his hands he called the rest of his players to him. The run was over.

Alred began to make his way over from the touchline. After a few short words from Johnson, the huddle broke apart. Twenty-nine players headed for the showers. One remained.

Wilkinson.

At twenty-four, he was widely regarded as the best stand-off that England had ever produced. Indeed, many regarded him as the best player the world had ever seen. He was meticulous in everything that he did – from his training, diet, game preparation and analysis to the way he masterminded England’s structure and play on the field. Never before had rugby union seen such a dedicated professional. He was the poster boy of English rugby and was adored across the country for his good looks, polite, unassuming manner and his virtually unerring excellence on the field – even though the latter was developed and maintained at a great personal pr

ice.

He began to walk slowly around the pitch, gathering up all the balls that had been used during the run-through before picking up a bag of extra balls that had been left on the pitchside. Alred met him there with a small blue kicking tee and they set off together towards the posts at the far end of the pitch.

As Wilkinson placed the ball on the tee – the seam of the ball aimed directly between the uprights, the ball tilted fifteen degrees to the left to open up the sweet spot for the first metatarsal bone in his left foot – he took a deep breath and slipped comfortably into a well-worn routine. In the secular world of sport, the two tall uprights and intersecting crossbar that made up a set of rugby posts were Wilkinson’s altar; the metronomic routine that he went through as he placed first one ball on the tee and then another and another and another, with each flying straight and true between the uprights, was his carefully fashioned and delicately refined ritual.

The job of the rugby goal-kicker can be one of the loneliest in world sport. Dave Alred, who had helped Wilkinson to create and then hone his systematic technique, was there to ensure that his protégé was never alone; no matter the circumstances, no matter the conditions, no matter the pressure, he would never be alone when kicking for goal. The routine would always be there to keep him company, to focus his mind – not on the boiling mass of humanity in the stands around him, not on the roaring of tens of thousands of voices or the rolling clacks of hundreds of cameras aimed solely at him, or on the scowls and sledging and the sly digs from the opposition, but on the quiet practice fields, where his thoughts were calm and focused, where the only sound to be heard was of wind in the trees, occasional birdsong and the thump of a ball being perfectly struck on the sweet spot.

Wilkinson straightened, checked his alignment of the ball, took two steps backwards and then one to his right and leant forwards, his knees bent, his hands gently cupped together in front of him.

White Gold

White Gold